Every year, 11 million metric tons of waste enters our oceans from the US, 6.6 million of which remains in coastal waters. If you’ve gone to the coast recently, you might have seen remnants of this – plastic bottles and bags littered across a beach or a marina.

Ocean cleanup projects have existed for years, but many require a manual component. What if this could be automated, or left on autopilot?

This is what Michael Arens and his team is working on — an autonomous robot that skims the water and pulls in trash to clean our coastal regions. What started as a high school passion project has become one of the Midwest’s newest climate robotics startups, Clean Earth Rovers.

The Spark: A High School Classroom

Michael Arens was shocked. Sitting in his high school public speaking class, he had just heard his classmate present on the issue of ocean plastics. Even though he’d been aware of climate change, he was particularly struck by this issue. Almost 8 tons of plastic enters our oceans from the US every year. How had he never known? The thought of plastics ruminating in our oceans for millions of years deeply troubled the 18-year-old.

The worries never left him. That summer before college, Arens prototyped and built an early version of a robot that skimmed water with scrap metal that he tested in a pool.

Like most first drafts, it failed.

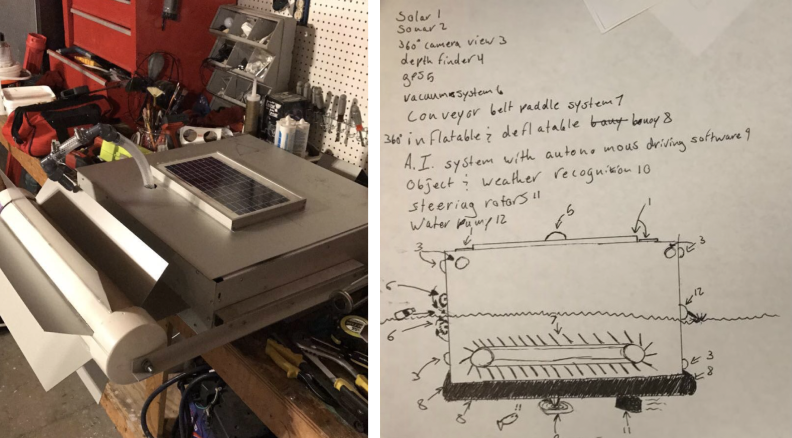

(Left) Building the early prototype (Right) Early design drawings

(Left) Building the early prototype (Right) Early design drawings

However, this didn’t deter him from believing in the idea itself. Even after Arens went off to Xavier University in 2017, he continued to think about the problem, ideating casually on his own.

In 2019, his junior year, an opportunity presented itself: the Big East Pitch Competition, where students pitched their idea for a $10,000 grand prize.

Arens competed, pitching his early ideas for an autonomous water cleanup rover. He cleared the first round… and the second round… but wasn’t chosen for the final round. Despite not winning, competing launched him into a world of opportunity. He caught the attention of professors and advisors, who saw promise in his idea and encouraged him to take it more seriously.

And so he did.

Starting Small

He found a co-founder, David Constantine, and joined a local accelerator that taught them startup foundations.

That summer after the accelerator, Arens and Constantine realized they needed something to show to help people easily visualize their product. That’s when they built a second prototype made of wood and self-built conveyor belts with a measly $300. As scrappy as it was, it did its job and gave external parties the gist of their vision.

The following Fall, they did an independent study dedicated to working on the idea and gaining traction through the entrepreneurship program at their university.

Their vision at this point was a massive, 60 ft. by 60 ft. robot that would autonomously scan the ocean on month-long expeditions. It would then return to land loaded with trash, which the company would recycle and monetize.

Over time, they realized this wasn’t economical since the margin on recyclables are extremely low, while the manufacturing and maintenance cost of a big rover is very high. They decided to “start small” - they narrowed their scope to picking up small trash along the coast on a daily instead of monthly basis. This allowed them to reduce the size of the robot to 5ft. by 5ft. This made it much easier and cheaper to build and iterate, making the economics more attractive to investors, grants, and customers.

Finding Product-Market Fit

In the Spring of 2020, they participated in a entrepreneurship program with the University of Cincinnati, through which they received their first check. They also added 2 new members to the core team: Chris Petersen (CRO), an experienced entrepreneur and professor of entrepreneurship at the University of Cincinnati, and Jonathan Rosales (CTO), who had his undergraduate degree in robotics and Masters in Mechanical Engineering from the university.

Concurrently, the world was sobering to the realities of COVID-19. Despite the challenges of operating virtually, the team forged onwards, joining the ICorps@OH program. Through this, they validated their new business model and began finding product-market fit by validating their hypothesis from potential clients.

The team plans on primarily targeting marinas and coastal businesses, who are most heavily impacted by coastal pollution: trash finds its way to these businesses’ docks, where it gets stuck. Conversations with 150 marinas revealed that typically, multiple employees have to spend 30 minutes to 2 hours each day manually removing the trash. Their robot not only frees employees of a menial task, but cleans more efficiently than people – after the rover cleans, it can be emptied in 5 minutes or less.

Arens says Clean Earth Rovers provides 3 key value propositions for marinas and coastal businesses: 1) removing trash, 2) increasing employee efficiency - allowing them to have more time maintaining the docks and interacting with customers, and 3) providing intelligence on water quality and safety.

In addition to the trash removal service, the team’s customer research revealed that municipalities regularly ask marinas for water quality data. Based on this, the team plans to collect and monetize water quality data in 2 ways: 1) stream data to help marinas better understand water quality and safety, and 2) provide the data to researchers and municipalities that are seeking more affordable widespread solutions.

Their data play could be extremely lucrative; Arens said the team realized the “ginormous lack of infrastructure when it comes to nearshore monitoring” during customer research. Municipalities, research institutions and homeowner associations need this data to gather insights and make better decisions, but nowadays their best bets are either fixed location monitoring sensors or hiring people to manually collect the data. This data alerts communities of events like red tide and blue green algae blooms, which result in widespread destruction of some of the most powerful natural carbon sequestration agents: kelp and seagrass. Not only does this impact carbon release, it also destroys crucial fish and marine life habitat.

Clean Earth Rovers uses a hardware-as-a-service model, where customers rent their robot for a fixed monthly fee, instead of a more traditional CapEx model in robotics where the customers would buy the rover as an upfront investment. CapEx works well for manufacturers, which most robotics companies work with, because they are used to making big asset investments. However, hardware-as-a-service is far more accessible to coastal businesses; they are already paying for employees to remove trash on an hourly or daily basis, and this is much less than a large upfront payment.

Developing the Rover

Alongside business development, the team used their grant from University of Cincinnati to iterate on their prototype. They found a kit supplier that allowed them to build a reusable frame that sped up iteration and testing. They tested various conveyor belt and lift designs until they settled on their current design, which looks like this after 6 iterations:

New rover prototype.

New rover prototype.

The rover autonomously navigates around the marina using its onboard LIDAR for obstacle detection and localization. It collects trash by funneling it to the center of the device and storing it in a large bag. It’s also equipped with sensors for water quality data collection and a camera that live streams a video feed to the user app.

Once the rover returns to land, a human operator can take off the bag and discard it in a dumpster. The entire human-interaction process is designed to take 10 minutes or less.

The rover is designed to be a good citizen in the marina - it operates at a safe speed that allows for quick stops to avoid damaging the docks or boats and has an emergency stop if any collision is detected. It also follows the boating standard and goes to the right when passing a boat of the opposite direction.

One interesting design lesson the team learned is from the collection capacity - the rover can hold as much as 100 pounds of trash, but the team found that it was very hard and even dangerous for a person to lift this much trash from the water because they could easily fall into the water if they lose their balance or hurt themselves by lifting this much weight. So the team ended up reducing the capacity to 75 pounds.

The rover is also designed to be very easy to set up - it comes with a mobile app that allows the user to set some waypoints. The rover will follow the waypoints, avoid obstacles and replan a return path if the battery is low. The app also allows the user to view a live feed of the water quality metrics and video.

By getting to the customer as early as possible, failing and iterating fast, The team’s customer-centric product design approach has paid off. Today, Clean Earth Rovers is working on their first pilot in San Francisco.

Looking Forward

Worldwide, tens of millions of tons of waste gets dumped into the ocean every year, for which the US is a big contributor. As a near-term goal for the company, Arens hopes to remediate at least 25% of the total US contribution to ocean waste by deploying rovers to the 1400+ marinas across the country. For him, the biggest challenges on the horizon include recruiting with limited funding as well as keeping improving the business model.

To those interested in helping fight the climate crisis, he says to “find something you’re truly passionate about… It’s not a quick path to success, and there are a lot of barriers and hurdles you have to get through to get to the fun end goal of things”. He also suggests not to “give up too soon” and try to utilize the community and resources around you to look for solutions.

The Takeaways

Here are our key takeaways from Aren’s story:

- Inspiration can come from anywhere, anytime! For Arens, it was a high school classmate’s speech. It’s important to keep an open mind and question the foundations of our knowledge. Don’t let age deter you – even a high schooler with dedication could turn into something great.

- Perseverance, passion, and grit is meaningful. Despite all the people who told Arens that his idea wouldn’t work since 2016, he pushed forward, and Clean Earth Rovers continue to exist today. The company would not exist without his 6 years of continued effort.

- You don’t need a hardware background to start a robotics company, but it does have a higher technical bar. Putting together the right team with the necessary technical and business backgrounds is crucial to the company’s success.

- Recruiting is a common pain point across all the climate robotics companies we’ve talked to so far.

If you are interested in getting involved in climate robotics, we hope you find these takeaways helpful! Don’t forget to like this article at the bottom!

This is the third article in our Founder Spotlight series. Check out our other blogs here. Do you know a cool company or person actively working on climate robots? Let us know!

Acknowledgement

Huge thanks to Michael Arens for his time, patience, and openness. Thanks Sherry Chen and Robert Eng for their suggestions and editing!